You are here: Home >

History of Franklin County Florida

Apalachicola

Apalachicola enjoys a history rich in maritime culture and natural resources. Apalachicola is an Indian word for “land beyond” or “those people residing on the other side” or “friendly people over there.” There were once more than 40,000 Indians in this region. The first Apalachicola Indians were members of the Mississippian Culture. Later tribes included the Seminoles and Creeks. The first non-natives were the Franciscan friars who arrived from Spain in the 1700s. Early trade between the Spanish and Creek Indians was in produce and fur.

Apalachicola was established in 1831 and grew quickly as a cotton shipping port town. By the mid 1800s, Apalachicola’s waterfront was lined with brick warehouses and broad streets to handle the loading and unloading of cotton. At one point, Apalachicola was heralded as the third largest port on the gulf. Steamboats laden with cotton came down the river and were unloaded on the docks. From there, the cotton was reloaded onto shallow-draft schooners that shuttled the cargo to ships waiting offshore. The invention of refrigeration in 1851 by Dr. John Gorrie proved revolutionary not only to Apalachicola but to the entire nation. Gorrie invented refrigeration and a form of air conditioning while attempting to treat yellow fever victims. Another Apalachicola resident, Dr. Alvin Chapman, was a mid 1800s botanist and author who also received international notoriety for his study of southern plants. A museum dedicated to his work exists today in Apalachicola.

Apalachicola was established in 1831 and grew quickly as a cotton shipping port town. By the mid 1800s, Apalachicola’s waterfront was lined with brick warehouses and broad streets to handle the loading and unloading of cotton. At one point, Apalachicola was heralded as the third largest port on the gulf. Steamboats laden with cotton came down the river and were unloaded on the docks. From there, the cotton was reloaded onto shallow-draft schooners that shuttled the cargo to ships waiting offshore. The invention of refrigeration in 1851 by Dr. John Gorrie proved revolutionary not only to Apalachicola but to the entire nation. Gorrie invented refrigeration and a form of air conditioning while attempting to treat yellow fever victims. Another Apalachicola resident, Dr. Alvin Chapman, was a mid 1800s botanist and author who also received international notoriety for his study of southern plants. A museum dedicated to his work exists today in Apalachicola.

By the eve of the Civil War in 1861, Apalachicola was the sixth largest town in Florida with 1,906 residents. Around that same time, Apalachicola had a racetrack, the Mansion House, which offered balls, socials and gambling, an opera house and a newspaper.

By the late 1800s, railroads had expanded throughout the U.S. carrying cargo farther and faster. As a result, the steamboats slowly disappeared from the Apalachicola River and the timber industry boomed, fueled by seemingly endless miles of rich forestland. Lumber mills were established and lumber magnates built many of the historic homes that line the town’s streets today. Late in the 19th century and on into the 20th, both Apalachicola and Carrabelle produced large quantities of lumber and turpentine.

Click here to learn more about Apalachicola history and historic landmarks.

Carrabelle

The history of Carrabelle is a story of Indians, shipping, bootlegging, logging and even war.

Rio Carrabella, or “beautiful river” was the early name of Carrabelle. Early settlers in the area, both Indians and early Europeans, hunted game for food and furs, which were then shipped out of St. Marks.

Carrabelle became a city in 1881. Carrabelle’s boom time, however, actually happened prior to that. The Carrabelle area flourished after the Civil War when lumber and naval stores were the most important commodities. In 1875 the first lumber mill was established. Schooners would come through the pass and drop anchor behind Dog Island in Ballast Cove, so named because the ships would drop their ballast before sailing into Carrabelle to pick up their cargo.

The town’s proximity to the coast made it particularly susceptible to hurricanes. A series of hurricanes hit the area during the late 1800s. One that struck in 1899 destroyed much of the community. Following the hurricane, the town was rebuilt and the downtown relocated more inland to its present location.

In 1895 a lighthouse was erected just west of Carrabelle about a quarter of a mile from St. George Sound. It was known as the Crooked River Lighthouse. The historic lighthouse still stands today. The Crooked River Lighthouse Park and Keeper’s House Museum the original, historic Fresnel lens, an authentic period room from the first keeper, exhibits and gift shop.

In 1895 a lighthouse was erected just west of Carrabelle about a quarter of a mile from St. George Sound. It was known as the Crooked River Lighthouse. The historic lighthouse still stands today. The Crooked River Lighthouse Park and Keeper’s House Museum the original, historic Fresnel lens, an authentic period room from the first keeper, exhibits and gift shop.

By 1941 Carrabelle had become an important oil shipping port. Oil was shipped to Carrabelle, sent by pipeline to Jacksonville where it was loaded on ships for delivery to Europe. In 1942 Camp Gordon Johnston opened, originally as Camp Carrabelle, to train Infantry Divisions and their support units in amphibious operations. Occupying 165,000 acres of forest and coast in Franklin County, Camp Gordon Johnston oversaw the training of a quarter of a million troops and was the second largest installation in the state. The camp stretched from Carrabelle to Alligator Point, using area beaches and forests for training and maneuvers.

Click here to learn more about Carrabelle history and historic landmarks.

Dog Island

Dog Island’s place in Franklin County history has been that of a protective barrier for the mainland. The island is reported to have once had three lighthouses – all of which were destroyed by storms. The barrier island was also the quarantine area for incoming ships with a resident doctor.

After World War II Jeff Lewis, a Florida businessman, saw Dog Island’s potential as a vacation area. He purchased the island and then sold a portion of it to the Nature Conservancy. For a time, a ferry ran between Carrabelle and the island.

Alligator Point

Alligator Point and Bald Point were inhabited 3,000 years before the Spanish arrived. In the mid-1800s and early 1900s, fishermen established seineyards at Bald Point. Evidence of the early turpentine industry is evidenced by pine trees that feature “cat face” scars. Bald Point was the site of military maneuvers during the WWII era.

©State Archives of Florida

Lanark Village

Lanark Village, located on the gulf about four miles east of Carrabelle, began as part of a promotion plan carried out by the Georgia, Florida and Alabama Railroad. It became a fashionable resort for people in nearby counties. The Lanark Springs Resort included a two-story hotel. A swimming area was fenced near shore where tourists could swim in a large freshwater spring emerging into the salt water of the bay.

During WWII Camp Gordon Johnston was built at Lanark Beach for use as an amphibious training facility. More than 25,000 trainees passed through the camp with about 10,000 housed there at a time. For many it was the last stopover before going to the Pacific or European theaters. Many of the officers’ quarters still exist today in the Lanark Village retirement community.

Eastpoint

Eastpoint was founded by a communal religious group. Prominent among the early settlers was the Brown family. The Browns, along with five other families, traveled down the Chattahoochee River from Georgia. The families established a group called the Co-Workers’ Fraternity which farmed the land, harvested seafood, worked the lumber industry and shared the profits. Rebecca Wood Brown served as Eastpoint postmistress from 1898 to 1938. Eastpoint’s first post office was located in the Brown home. Descendants of the Brown family still live in Eastpoint.

St. George Island

The history of St. George Island is colored with pirates, Indians and shipwrecks. The Creek Indians first inhabited the island as early as the 1600s. The Indians were aggressive traders and commerce flourished from the St. Marks River around and up the Apalachicola River.

The arrival of the Europeans to the island was followed by intensive struggles for control of the area. Pirate Captain William Augustus Bowles led the Creek Indians in their defense against the Spanish and French in the late 1700s. Legend has it that before Bowles died he buried a treasure somewhere on the island.

The arrival of the Europeans to the island was followed by intensive struggles for control of the area. Pirate Captain William Augustus Bowles led the Creek Indians in their defense against the Spanish and French in the late 1700s. Legend has it that before Bowles died he buried a treasure somewhere on the island.

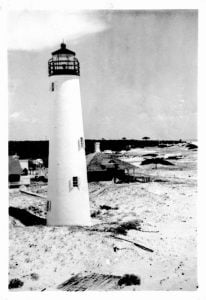

After the Forbes Purchase in 1803, commercial sailing traffic increased and a lighthouse was built on the west end of the island, which is now Little St. George Island. Following years of coastal erosion the Cape St. George Light toppled into the gulf in 2005. It has been rebuilt by lighthouse enthusiasts in its present location in the center of the St. George Island business district. It is the centerpiece of the island’s Lighthouse Park along with the Keeper’s Museum.

St. Vincent Island

St. Vincent Island was named by Franciscan friars who, around 1625, were moving westward through the Apalachee territory establishing missions. St. Vincent was part of the 1803 Forbes Purchase. In 1907 the land was sold to Dr. Valentine Mott Pierce, a patent medicine millionaire, who kept the island as a summer resort. Exotic animals were imported to the island and, for awhile, the island was run as a game preserve. Of all the exotics imported to the island only the Sambar deer remain today.

In 1968 St. Vincent was purchased by the Federal Government for use as the St. Vincent Island National Wildlife Refuge.